8th June 2024

A pingo is a geological phenomenon found in some of the coldest parts of the world. It is a small, dome-shaped hill that forms on flat areas of permafrost when water from an underground aquifer freezes into a lens of ice below the surface. The overlying soil and sediment is pushed upwards by the pressure of the expanding ice and each time the lens thaws and freezes with the seasons the hill grows a bit higher. Pingos can grow up to 70m (230 ft) in height and have a diameter of 1000m (3280 ft).

Nowadays, there are more than 11,000 active pingos on the planet, many of which are found in north-western Canada – in fact ‘pingo’ is a Canadian Inuit word meaning ‘small hill’ – with others in Alaska, Greenland, Siberia, and the Tibetan plateau. The remains of ancient pingos can be found further south in places where the ice sheet retreated at the end of the last ice age, 10-12,000 years ago. One such place is located in deepest Norfolk, UK, where evidence of pingos can be found all over the Norfolk Wildlife Trust’s nature reserve at Thompson Common. These take the form of distinctive circular ponds formed when the ice lens finally melted away and the hill collapsed to form a crater that was later filled with water.

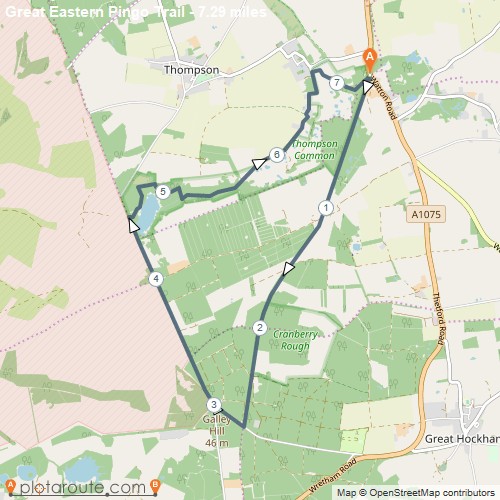

A seven mile (11 km) walking trail has been waymarked through the area, giving an opportunity to view a selection of these pingo ponds and the rare animals and plants that have made them their home. The Pingo Trail, or to give it its full name: The Great Eastern Pingo Trail, is a circular walk, so it can be started anywhere along its length. The most convenient place is the car park near the village of Stow Bedon. Without a car the Pingo Trail is not the most convenient place to get to – it took me two trains, a bus, and a 1.7 mile (2.8 km) walk – but once there you can set off in any direction. The signposts say it is an eight mile (13 km) loop but measuring it on Google Maps it is only seven miles (11 km) in a roughly triangular shape.

I decided to walk in a clockwise direction and set off south along the bed of an old railway line. This was once the Thetford, Watton and Swaffham Railway (later the Great Eastern Railway) and was in operation from 1869 until 1965. It was known locally as the ‘Crab and Winkle’ line due to its use by holidaymakers on the way to the North Norfolk coast, which is well known for its shellfish. Nothing remains of the railway now except the gently curving footpath that is a tell-tale sign of a disused line.

This early part of the walk headed straight into mature wet woodland and, with nesting activity at its spring peak, the woods were full of bird song. All the expected woodland inhabitants were present, and I took my time along there. As well as birds there was also an abundance of plants. I have only recently developed an interest in botany, but it has already opened up a whole new world for me. Whereas previously I had regarded plants as a mere background for more interesting wildlife, I now take much more notice of my surrounding vegetation, and I have started making a greater effort to identify it. Mostly I cheat by taking a photo on my phone and letting an ID app do the heavy lifting, but I’ve also purchased a good field guide to double check my efforts and, very occasionally, I’ll use it to ID plants the old-fashioned way. On the Pingo Trail I manage to put names to Wood Avens, Heath Woundwort, Water Violet, Water Forget-me-not, Amphibious Bistort and extensive displays of Foxgloves, among others. I also saw some tropical-looking ferns and primitive Horsetails, the species ID of which is currently beyond my (and my app’s) capabilities.

The names of some of these plants give away the fact that this is a watery habitat in the otherwise dry and sandy region of Breckland, the area of heaths and forestry plantations that straddles the border between Norfolk and Suffolk and lays claim to Britain’s lowest rainfall. This northern part of the Pingo Trail passes through Stow Bedon Common, and the woods here feature numerous ponds and flooded areas alongside the path. These don’t look like obvious circular pingos though, and I didn’t get to see any of those until later. The trail here was a bit muddy in places due to the wet Spring we have had this year, but it was still easy to walk.

In the middle of the railway section the trail crosses the more open country of Breckles Heath, with large stretches of grassland and a meadow filled with Highland Cattle. I saw a few Red Deer here, though fairly distantly – a female with a fawn, and then two females together.

The morning had started out cool but sunny and had gradually clouded over. By late morning, as if to mock the Breckland’s reputation for dryness, I was hit by the first of some Summer showers. Fortunately, the path headed back into woodland and I was somewhat sheltered by the trees.

On the southern section of the ‘railway line’ I passed through an area called Cranberry Rough. This was another area of wet woodland where wild cranberries grow, but I didn’t see any on this occasion. 10,000 years ago the retreating glaciers left a large lake here which persisted through Tudor times before finally silting up and becoming a swamp. In the 18th century it was drained via a network of dykes to form agricultural land, but eventually it proved too difficult to keep it dry and it reverted to swamp again until, in 1961, it was designated as a Sight of Special Scientific Interest and protected for the rare plants and invertebrates found here. The most obvious invertebrate on the day I visited was the mosquito – not particularly rare and definitely not in need of protection!

The path had been fairly wide when I started but became increasingly narrow with encroaching Summer vegetation. This was now soaked by the rain and was impossible to pass through without getting wet trousers. Fortunately, I soon reached the end of this section and turned onto a short stretch of paved road followed by a wide forest track heading north through commercial pine plantation. This was an ancient Roman road and is now part of the Peddar’s Way and North Norfolk Coast National Trail that runs from the Suffolk border in a straight, diagonal line across the county to, and then along, the North Sea coast of Norfolk.

The rain had stopped by then and I quickly dried out again. A postman in a van drove past and then, presumably having delivered to a remote house in the forest, drove back the other way. This was the first person I saw since setting off.

Some fenced off land immediately west of the path belongs to the Ministry of Defence and signs warn that it is a military firing range. This is the edge of the Stanford Training Area – a large part of the Brecklands used for training by the army, marked in red as ‘Danger Area’ on the Ordinance Survey maps and inaccessible to civilians. A few years ago I was walking along a forest track in the Brecks when a jeep filled with Gurkhas screeched to a halt and asked me for directions. They had driven out to the Breckland town of Brandon and couldn’t find the way back to their base.

A couple of kilometres along the Peddar’s Way the trail turned right again and entered the Norfolk Wildlife Trust reserve of Thompson Common, where I arrived at Thompson Water. This is a man-made lake formed in the 1840s, though I am unable to find any information as to why it was formed. It seems strange that an artificial lake was created here at the same time as a natural lake dating back to the ice age was being drained and ploughed only a stone’s throw away, but I expect they knew what they were doing.

By the time I arrived at Thompson Water I was getting hungry and was pleased to find a tiny birdwatching hide on the edge of the lake that was a perfect place to stop for lunch. It was one of the most basic hides I’ve ever sat in, but it provided what must have been the only dry seat for miles around. A pair of Marsh Harriers flew low over the reeds fringing the lake, while numerous Barn Swallows, House Martins and Swifts took advantage of the improving weather to hawk for insects over the water. Otters are frequently seen here, but not by me on this occasion.

Immediately after leaving the hide I found my first pingo ponds, easily recognised by their circular shape. By then the sun was shining and the trail continued through some beautiful deciduous woodland, winding sinuously through the trees in complete contrast to the long, gentle curves of the railway line and the ruler-straight Roman road of the Peddar’s Way.

Thompson Common nature reserve protects the majority of the remaining pingo ponds. Historically there were many more in the wider area, but previous generations filled them in and ploughed them over for agricultural use.

As well as these geological features, the reserve also protects some unobtrusive but very rare wildlife, most prominently the Northern Pool Frog. This is Britain’s rarest amphibian and it became extinct here in the mid-1990s, with Thompson Common being its last known UK location. At the time it was thought to be an introduced species, so no efforts were made to conserve it. It was only after it became extinct that they realised it was in fact native to Britain and a project was planned to re-introduce it.

Between 2005 and 2008 frogs were brought over from Sweden and a colony was established at the mysterious ‘Site X’. From these frogs a second population was re-created at Thompson Common. To reduce disturbance, they were introduced into pingo ponds in a part of the reserve inaccessible to the public, in the hope that their increasing population would eventually see them spread over the entire area. The project has so far been successful, despite a drought in the summer of 2022 which greatly reduced their numbers, but it is still not yet possible for visitors to find them along the Pingo Trail. Hopefully I’ll get to return in the future to hear the Pool Frog chorus.

Other tiny-but-precious creatures for which Thompson Common’s pingo ponds are a British stronghold are the Scarce Emerald Damselfly and the slightly less glamourous-sounding Pond Mud Snail. I didn’t see either of these but, in the warm sunshine, invertebrate life became more active as I headed towards the end of the trail.

The winding path left the woods and came out onto open grassland. There were more pingo ponds there, with a noticeably different aquatic flora away from the shade of the trees.

Three Red Deer stags grazed not far away, their weedy-looking antler starter kits beginning to grow in preparation for the Autumn rut. They may be happy to feed together for now, but come October they will become fierce, testosterone-fuelled rivals.

From this meadow I passed through a gate and onto a narrow, traffic-less country road that ran for a short distance between cottages. Up until this point the trail had been well waymarked and easy to follow, but some scoundrel had removed the waymark that pointed off the road and back into the woods. So, I continued along the road and, realising I had gone wrong, turned right and followed the road back to the car park where I started.

Not wanting to miss out any of The Great Eastern Pingo Trail, I followed the waymarks from the car park in an anti-clockwise direction along the trail until I reached the narrow road where I had gone wrong and, from there, I backtracked to the car park to complete the trail. I’m glad I made the effort to find this final stretch as it held some of the most attractive sights of the walk, with more woodland and some open, flowery grassland filled with Common Spotted Orchids and Southern Marsh Orchids (which I could now confidently identify due to my newly-acquired status as an expert botanist!). And, of course, there were many more pingo ponds of varying size and character.

The Pingo Trail is short and easily walked. It doesn’t present any great hiking challenges, but it holds an intense concentration of nature in a small area for anyone prepared to do a little research and take the time to look carefully and appreciate the small stuff. I definitely intend to return there occasionally to see what can be found as the seasons change and, if nothing else, I’m determined to catch up with those Northern Pool Frogs.

7 miles; 11 km; 6.5 hours

Leave a comment