“The weirdest bird’s-nesting expedition that has ever been or ever will be.”

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

The “worst journey” referred to in the title was a kind of side quest to Captain Robert Falcon Scott’s ill-fated 1910-1913 voyage to the South Pole aboard the Terra Nova. Published in 1922, it was written by the wonderfully named Apsley Cherry-Garrard (or Cherry to his friends) and recounts a winter trek from the expedition base camp to an Emperor Penguin rookery some 108km (67 miles) away, to collect eggs for scientific research (and breakfast, probably).

At the time of the expedition, a scientific theory known as the Recapitulation Theory was doing the rounds. It posited that, for any given animal, the development of its embryo from conception to birth (or hatching) was a ‘recap’ of the process of evolution that had produced that animal. By studying embryos at different stages of their development, scientists thought they could reveal insights into the process of evolution itself. It was thought (incorrectly) that the Emperor Penguin was “the most primitive bird in existence”, so studying its embryo would reveal the secrets of avian evolution.

As anyone who has watched any of the multiple penguin documentaries on TV will know, Emperor Penguins nest in the depths of the Antarctic winter, when the sun never rises, and all other creatures have headed to more moderate regions. If the eggs of these birds were going to be collected it would have to be in winter, while the main part of the expedition was safely ensconced in their over-wintering quarters, waiting for the Austral summer so they could begin the attempt on the south pole.

The trek was led by Edward Wilson, chief scientist aboard the Terra Nova, and he chose to take with him his assistant zoologist Apsley Cherry-Garrard, and polar legend Henry ‘Birdie’ Bowers. Scotsman Bowers came from a military background and, though only 5’ 4” (162cm), every account of his polar exploits portrays him as almost superhumanly tough, resilient, dependable and cheerful.

At 24, Cherry-Garrard was one of the youngest on the expedition, as well as one of the most intellectual, hard-working and popular. These were the three men who were to embark upon The Worst Journey in the World – or The Winter Journey, as it is more properly known.

Often described as the greatest travel book ever written, this was one I had been meaning to read for years. My recent trip to northern Scandinavia gave me the perfect opportunity. If the weather conditions to which I was subjected became too much to bear, I could open the pages and realise that what I was experiencing was nothing compared to what these guys suffered. And suffer they most certainly did! All polar exploration up to that point had been during the summer, which is dangerous enough. This was to be the first time explorers had spent any length of time in the open landscape of the Antarctic winter, with just a tent to sleep in, and hauling all their equipment on sledges. At the time, it was thought to be the worst climatic conditions to which any human had been exposed for a prolonged period of time.

They were away from the warmth and safety of the base hut for a total of five weeks. The hike to the penguin colony took 19 days, hauling two sledges, each measuring 2.75m (9 feet), and with a total weight of 343kg (757lbs): 116kg (253lbs) per man.

As it was winter, the journey was made in almost complete darkness and in temperatures ranging from -44°c (-47°F) to -61°c (-77.5°F). Because of these low temperatures, the snow didn’t melt under the sledge runners like it normally would, to allow a smoother glide over a thin liquid film, but instead it formed small granules that made it more like dragging the sledge over sand than over slippery ice. In consequence, it was too difficult for the three of them to haul both sledges tied together, and they had to move them one at a time, going back each time for the other one. This made the walking three times longer than expected and some days they would only manage 2.4km (1.5 miles) of walking. On the best days they would still only do 12km (7.5 miles).

Along the way they were constantly blighted by a smorgasbord of horrors: crevasses, fog, blizzards, exhaustion, frostbite, stomach cramps and dysentery from eating mostly fat, snow blindness, optical illusions and hallucinations were all routine. At one point it was so cold their teeth shattered. That’s not a typo – we’ve all been so cold that our teeth chattered, but never shattered! That’s a whole different level of cold.

And that was just during the ‘day’, while they were marching. The ‘nights’, when they tried with little success to sleep, were even worse (don’t forget there is no real ‘night’ and ‘day’ here. It was all polar night. All darkness). To quote Cherry:

“The day’s march was bliss compared to the night’s rest, and both were awful.”

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

Setting up camp every night with cold, blistered, frostbitten fingers would be a prolonged agony. Sweat would freeze almost instantly on clothes and sleeping bags, turning them into hard, solid boards. Getting into a sleeping bag would take an hour every night, beating the opening until it was flexible enough to start crawling inside, then using body heat to soften it up, bit by bit, until the human could gradually slide inside. Getting into clothes required a similar process of pummelling and thawing. Spending too long in one position would freeze the body into a solid cocoon of icy fabric, preventing any movement. In the morning it would take three to four hours to get ready again.

Even though this book was written ten years after the event, it contains a remarkable amount of detail and is arguably the best first-hand account of self-inflicted human suffering ever written.

Once they reached the Emperor Penguin rookery they built an igloo of rock, ice and snow, and used their tent to stow equipment. During the night the tent blew away in a hurricane. With no shelter for the journey back they realised they were doomed, and so contemplated their own deaths. They had got to the point of suffering were they literally no longer cared if they died, and they discussed whether to commit suicide or press on and die naturally. They somehow found it in themselves to carry on and, miraculously, found the tent half a mile away.

Eventually all three of them got back to the base hut. One of the things that really struck me reading this book is the orderliness, camaraderie and relative cosiness of life at the base hut contrasting starkly with the horrors of The Winter Journey. And ‘horrors’ is exactly the right word. Sometimes this book reads like a horror story, except it really happened, to actual flesh and blood people. Even Cherry himself agrees with me:

“Antarctic exploration is seldom as bad as you imagine, seldom as bad as it seems. But this journey had beggared our language: no words could express its horror.”

Apsley Cherry-Garrard

So what about the eggs then? Surely they got some eggs, and the journey wasn’t completely futile? Well, yes, they did. They collected five eggs and brought three of them back to the UK. The other two broke. Unfortunately, at the exact same time Wilson, Birdie and Cherry were going through hell on ice, science was moving on from the Recapitulation Theory and it was being thoroughly discredited. In fact, Cherry was treated quite shoddily by the curators of London’s Natural History Museum when he delivered the eggs in person. They showed little interest in the specimens and even less in the efforts required to obtain them. They still took them though, and the eggs reside there to this day.

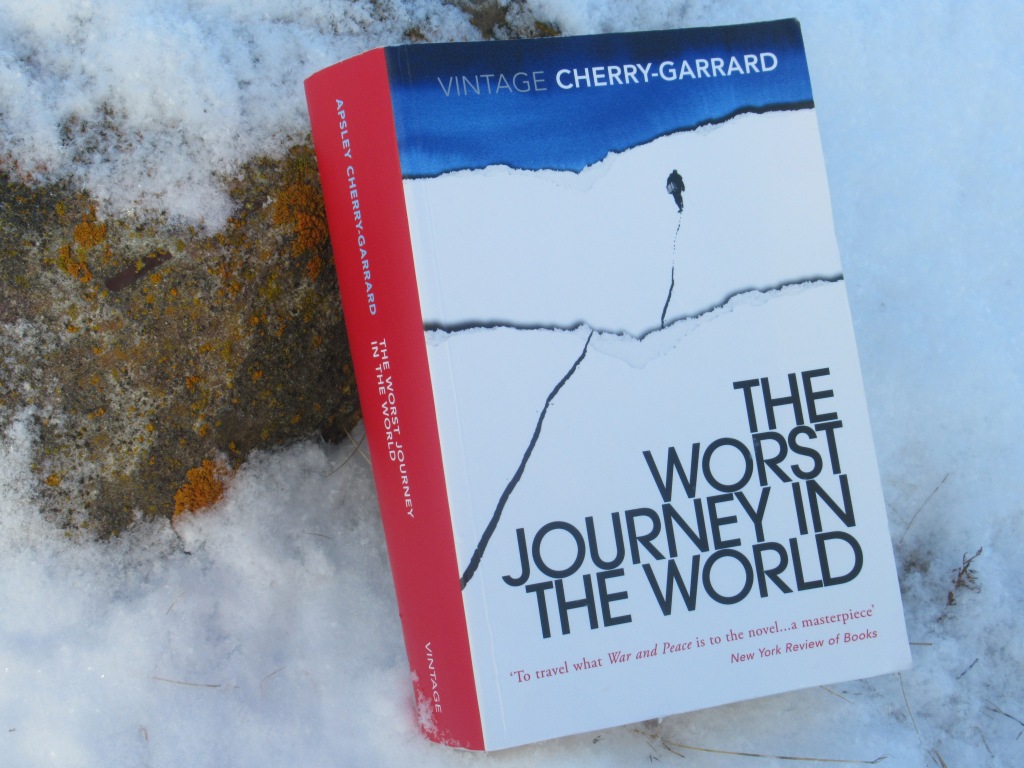

At 600 pages, this is a fairly hefty book, plus foreword and an introduction by Cherry’s biographer Sara Wheeler. This latest edition is published, appropriately, by Penguin. The account of The Winter Journey doesn’t start until almost halfway into the book, and I didn’t finish reading it until a month after I got back from the Arctic. There is a lot of detail here about the entirety of the Terra Nova expedition and the race to the South Pole. It’s a book in which anyone with a fascination for the history of polar exploration will enjoy losing themselves. If words like ‘pemmican’, ‘sastrugi’, ‘finnesko’, and ‘hoosh’ get your juices flowing, then this is the book for you. Others may find the detailed accounts of supplies, depots, and daily rations too much to bear, and long for him to get back onto frostbitten noses, missing toes, and bearded men dangling precariously into crevasses. However, unlike some books of this length, it never feels like a chore due to the plain-spoken language in which it is written.

Before the Winter Journey chapters, Cherry writes about the sailing from Cardiff to Antarctica via South Africa and New Zealand. He then describes the setting up of the base camp at Cape Evans and the elaborately planned provision of depots along the route which Scott and his team will follow to the south pole. This route started on the permanent ice barrier of the Ross Ice Shelf, before climbing up the Beardmore Glacier onto the solid land of the Antarctic continent itself. He gives vivid accounts of such day-to-day events as an entire team of sled dogs falling into a crevasse and having to be rescued one at a time, or in another incident, waking up in a camp on seasonal sea ice to find it breaking up underneath them, and needing to get off fairly sharpish. Along with equipment, dogs, sledges, and ponies, they jumped from moving ice chunk to moving ice chunk, all the while being stalked by spy-hoping Killer Whales waiting for a pony to slip into the sea. Yes, that’s right – ponies. Many of Captain Scott’s problems seem to be pony related. Who knew taking ponies to Antarctica would cause so many problems? *shrugs*

After the men of the Winter Journey returned to camp, the book goes on to describe Scott’s march to the pole only to find the Norwegian Roald Amundsen had got there a month earlier. The five man team all perished on the walk back. Cherry was part of the search team that found Scott’s tent containing his body, flanked by those of Wilson and Bowers – Cherry’s two companions on the Worst Journey in the World. Even the apparently superhuman Bowers turned out to be mortal after all. The other two explorers had died earlier on the march – Edgar Evans had succumbed slowly and increasingly painfully, and Lawrence ‘Titus’ Oates, realising he was slowing them down, had sacrificed himself with the famous words “I am just going outside, and I may be some time”, before walking off into a blizzard.

So out of the three Winter Journey participants, only Cherry could have written this account for only he made it home. For much of the book, especially the parts of the expedition which he didn’t personally witness, he borrows liberally from the journals, letters and published writings of the others. The narrative jumps freely between different writers until the reader no longer cares who is narrating each particular passage. This is never jarring but rather it helps to highlight just how much of a joint enterprise this was. They were all in it together, with everyone experiencing the same great hardships and small joys.

But while this book is primarily a catalogue of monumental human suffering, there are lighter moments too, such as a wildly anthropomorphic description of the devious mating habits of Adelie Penguins, an account of pupping season in a Weddell Seal colony, and the antics of the sled dogs. Although the latter mostly involves trying to chew their way out of their harnesses to kill things: penguins, ponies, each other.

Through all the hardship, what really shines through is the respect, admiration and love for one another that these explorers had. This is a book about camaraderie, self-sacrifice, hard graft in pursuit of a higher calling, determination in the sure knowledge of failure, and all of those clichés of stiff-upper-lipped heroism that characterised the Edwardian era. As with many British polar expeditions, the suffering ended in disaster.

When reading historical accounts such as this, it is only human nature to put yourself in their position and think about how you would have coped. In my case the answer is simple: I wouldn’t have coped at all. My cold fingers and toes in northern Norway were pathetic compared to the agonies described in this book, and I’m thankful that I’ll never have to go through what they went through. Reading history is always a good way to put our own existence into perspective. It can make us realise how lucky most of us are to be living in these times, and just how historically rare times like these are. I know many are still born into lives of pain, suffering and abuse, but for most of us born into the developed world in the late 20th/early 21st centuries, we don’t have a great deal to complain about compared to our ancestors.

So anyway, this review has gone on almost as long as the book itself. And if anyone complains that it contains too many spoilers… come on! It was published more than a century ago. How much time do you need?

Leave a comment